What is Retrograde Extrapolation? How Do Blood Tests Affect DWI Cases in North Carolina? Can They Prosecute DWI Cases with Low Blood Readings?

- Can They Prosecute DWI Cases with Low Blood Readings:

- Yes, Understanding there are Scientific Principles to Consider

- BAC Refers to Blood Alcohol Content

- BrAC Refers to Breath Alcohol Content

- Retrograde Extrapolation Can Be Complicated

North Carolina has some pretty complicated laws and rules in Court when it comes to Retrograde Extrapolation – John Fanney

When evaluating potential defenses to Driving While Impaired (DWI) cases in North Carolina, most defense lawyers always look to the breath or blood alcohol concentration reading as a sort of “bright line” test. That is, most of us look at the breath test slip brought to us by our client and use it as a way of determining if the case is defensible on the issue of whether a defendant had a particular breath or blood alcohol concentration (BAC). Indeed, this is a necessary step in the overall planning of defending against a charge of DWI.

The danger in using a “bright line” approach is that we may overlook ways to defend the case because the “number” is too high or may take things for granted because the “number” is low, only to have the State introduce evidence of a much greater number. This effort by the State to introduce a higher number comes in the form of the application of Retrograde Extrapolation.

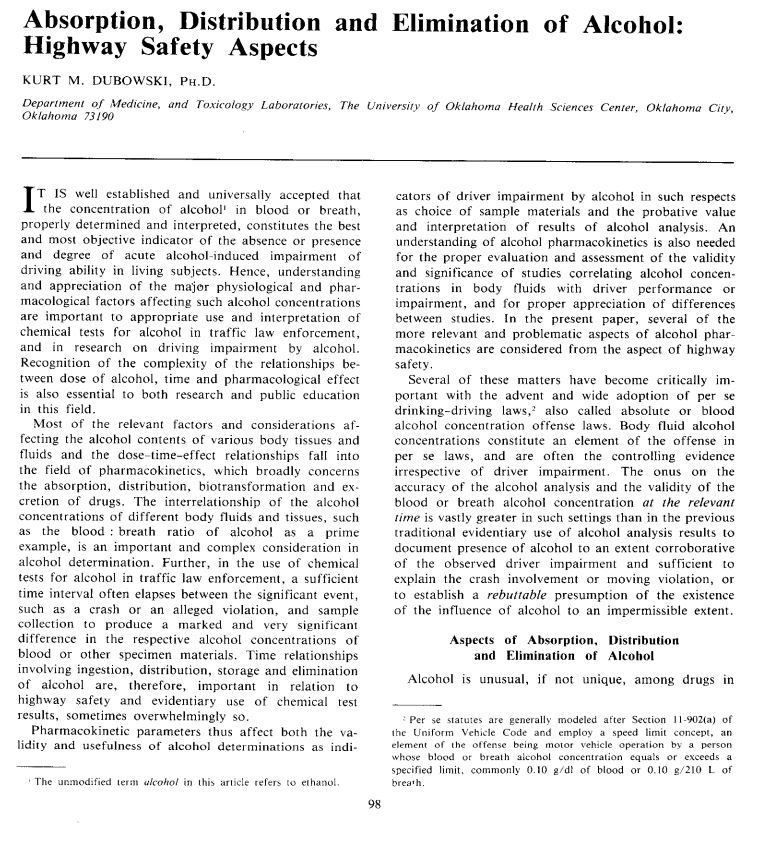

Extrapolation of a later alcohol test result to the time of the alleged offense is always of uncertain validity and therefore forensically unacceptable – Kurt M. Dubowski

The theory of retrograde extrapolation has probably been in existence as long as there have been ways to measure things with a numerical value and a desire to “know” what the value would have been at a more remote point in time. In the context of DWI cases, North Carolina courts have recognized the practice of retrograde extrapolation for decades.

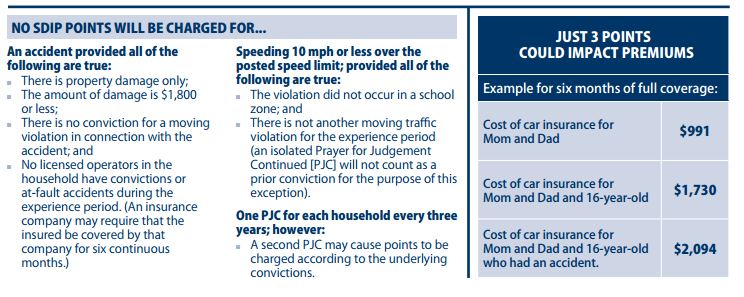

The use of retrograde extrapolation has increased greatly as the pressure by our Legislature and general public has grown to “rid our streets of drunk drivers”. For example, many prosecutors would previously elect to dismiss a DWI charge altogether or reduce the charge to a plea to Reckless Driving when the results of a breath or blood test were below a .08.

By now employing the theory of retrograde extrapolation, the State is greatly expanding the number of cases where it can increase the weight of evidence against a Defendant and expand the application of the second prong of North Carolina’s DWI statute to secure more convictions.

The application of retrograde extrapolation usually occurs in wreck cases, especially those involving deaths or injuries. The use of retrograde extrapolation highlights many of the procedural and evidentiary obstacles that defendants face in DWI cases. These obstacles include 1) dealing with assumptions in the State’s evidence; 2) establishing a contrary defense theory to the issue of “legal” impairment; and, 3) overcoming precedent case law intended to ease the introduction and use of certain types of evidence. This section discusses the basic principles of retrograde extrapolation and the problems associated with its practice. It will discuss legal and factual issues to consider in defending the retrograde extrapolation prosecution. Finally, this section will discuss the treatment of retrograde extrapolation by our appellate courts and suggest ways to successfully challenge its acceptance and use in our court system.

What is Retrograde Extrapolation?

Retrograde extrapolation is the establishing of a BAC at a point in time prior to the collection of a breath or blood sample from a defendant. The term “retrograde” is defined as “moving, occurring, or performed in a backward direction or opposite to the usual direction”. The term “extrapolate” is defined as to “project, extend, or expand (known data or experience) into an area not known or experienced so as to arrive at a usually conjectural knowledge of the unknown”. Simply put, the concept of retrograde extrapolation is, at best, an educated guess. It is this educated guess that is used by the State to convict defendants of DWI when a chemical analysis fails to show a BAC over the legal limit.

The Theory Behind Retrograde Extrapolation

Retrograde extrapolation is premised on two established facts regarding how the human body processes alcohol from the body. These are 1) that alcohol ingested into the body will reach a “peak concentration” following its consumption and 2) that alcohol is then eliminated from the body at a fairly predictable and constant rate. These two critical portions of an extrapolation analysis must be fine-tuned by factors relative to a particular person.

Factors include:

- The amount of alcohol consumed

- The type of alcohol consumed

- The drinking pattern of the drinking episode

- Consumption of food at or near the time of drinking

- The type of food consumed

- Gender

- Weight

- Age

- Experience with alcohol

- Mental state

- The duration of the drinking episode.

These variables are necessary to consider in establishing a time for the peak rate of concentration. Once a time for the peak rate is established, there is an application of an elimination rate. From there, an extrapolation can be performed with the results of a chemical analysis and the time span to a desired point back in time. This all seems like a straight-forward, reliable and predictable model on the surface. As is often said, “the ‘devil’, is in the details”. The details of this theory is what makes is unreliable in many applications.

There are numerous studies available regarding the science of alcohol consumption and elimination in the human body (see attached appendix). What is important to note is that there is neither a constant time by which the body reaches its peak alcohol concentration nor a constant rate of elimination of alcohol from the body. The time by which an individual may reach a peak rate of alcohol concentration has been found to be from to one-half hour to two hours or more following consumption for an individual with an empty stomach and from one hour to six hours for an individual on a full stomach. These rates vary widely and are subject to the variables listed above. The rates of elimination have been observed to be from 8 mg/dL/h or .008 per hour to 36 mg/dL/h or .036 per hour. Elimination rates are expressed scientifically as the number of grams per 100 milliliters per hour.

More importantly, studies have shown that elimination rates vary in an individual person from day to day. The long list of variables cited above influence these two critical factors for a reliable extrapolation. Studies further show that once the body begins to eliminate alcohol, it does not mean that one’s rate of elimination is constant. The body’s elimination rate is subject to change. There have been studies which indicate that, during the elimination phase, a person’s BAC may actually go up or “steeple” a number of times along the elimination curve. So, it is possible that a person’s BAC begins to go down, goes up again and then goes back down.

It is essential to determine the timing of peak alcohol concentration in order to safely assume a subject is in the elimination stage rather than the absorptive stage. Any extrapolation attempted while a subject is still absorbing alcohol will result in an unreliable and false conclusion. The administration of a chemical analysis, either by a blood sample, or by the Intoximeter EC/IR II rests on the assumption that the subject is in the elimination stage of processing alcohol through the body.

The myriad of assumptions and variables associated with retrograde extrapolation is what makes this theory of questionable value. In fact, some of the most well-known and respected experts in the field of blood alcohol research have expressed their own reservations on the usefulness of retrograde extrapolation. Dr. Kurt Dubowski, the virtual godfather of blood alcohol testing, once stated “no forensically valid forward or backward extrapolation of blood or breath alcohol concentrations is ordinarily possible in a given subject and occasion solely on the basis of time and individual analysis results”. See, Absorption, Distribution and Elimination of Alcohol: Highway Safety Aspects. A.W. Jones, a noted research scientist in the field of blood alcohol testing once termed retrograde extrapolation as “dubious practice”. Further, Jones also outlined problems in determining the post-absorptive state of the drinking driver by concluding “the status of ethanol absorption in drunk drivers at the time of the offense is a more difficult question to tackle”. Jones then recommended that, in order to avoid speculation over the absorptive state of the driver, states define the offense of drunk driving as having a certain BAC at the time of the breath test rather than the time of the driving. See, Richard Watkins & Eugene Alder, The Effect of Food on Alcohol Absorption and Elimination Patterns, 38 J. of Forensic Science 285-291 (1993) quoting A.W. Jones.

As North Carolina practitioners know, our State’s statute regarding breath testing does just what Jones has recommended. Our statute only requires the State to establish that the driver (or now defendant) had an alcohol concentration of .08 or greater at any relevant time after the driving. We know from the definitions found in our motor vehicle code that a relevant time after driving is ANY time after the driving that the driver has previously consumed alcohol remaining in his system. Yet, the State is often not satisfied with the number that is revealed by a breath or blood test. The number for the prosecutor is either 1) not over the statutory threshold for “legal” impairment; or, 2) not shocking enough for the finder of fact to find someone guilty of the charged offense. The State will often resort to expert testimony to overcome these perceived hurdles.

North Carolina Criminal Law Updates

North Carolina Criminal Law Updates